What becomes a legend most? Interview with photographer Nan Goldin

posted February 14, 2024 at 3:05 pm in Art, Feature, Interviews

What becomes a legend most?

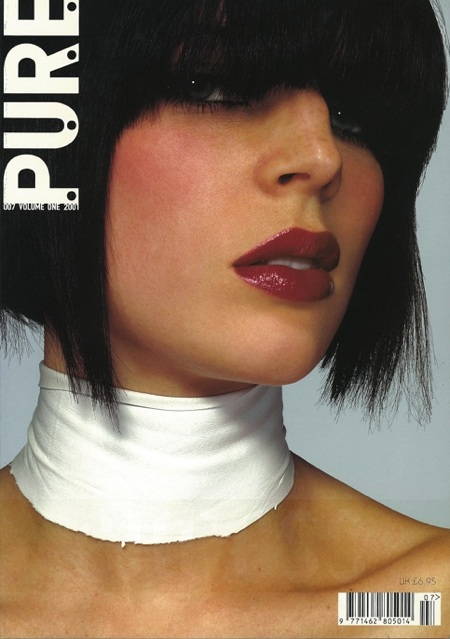

I have been sorting through my cuttings and notes recently and found the transcription of an interview I did with Nan Goldin in 2002 which I was commissioned to write for Pure magazine, and has until now, never been published, as, sadly, Pure folded before this piece could go to press.

I know I have subtitled this blog “My Literary Life”, but the work of Goldin, one of my favourite artists whose work has made such a great impact on me – I am an unabashed and unapologetic fan – and has, in my opinion at least, such a powerful narrative quality, I thought this blog would be a appropriate place to publish it.

I first encountered Nan Goldin’s work in 1990 when I saw an image of hers, David and Butch crying at the Tin Pan Alley, New York City, displayed in a show of fashion photography at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

This image of a woman in tears whilst trying to remain composed as Goldin takes her picture made a great impression on me. It stood apart from the other inclusions in the show, and was, I thought, an odd choice, not as it didn’t apparently fit the remit of the show, although I was delighted it had been included despite not having any overt fashion content, as this was my introduction to Goldin’s work. To me the image embodied the narrative power and qualities of the best literature; empathy and mystery. A depth charge went off in my head.

Then later on at the ICA, I saw Goldin’s book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (Aperture, 1986, first published in the UK in 1989 by Secker and Warburg), which I bought.

I was deeply impressed by Goldin’s startling talent and not only the brilliance of her images but by her sensitive and insightful introduction, which laid out quite succinctly what compelled her to document her world.

Discussing her sister Barbara’s suicide at the age of 18 (when Goldin was merely 11), she wrote, “When I was 18, I started to photograph. I became social and started drinking and wanted to remember the details of what happened. For years, I thought I was obsessed with the record-keeping of my day-to-day life. But recently, I’ve realised my motivation has deeper roots: I don’t really remember my sister.

“In the process of leaving my family, in recreating myself, I lost the real memory of my sister. I remember my version of her, of the things she said, of the things she meant to me. But I don’t remember the tangible sense of who she was, her presence, what her eyes looked like, what her voice sounded like. I don’t want to be susceptible to anyone else’s version of my history. I don’t ever want to lose the real memory of anyone again.”

However, many of her friends that she documented so intensely were lost to early deaths – often from AIDS-related illnesses. A few years after the Ballad was published, she wrote in her introduction to her monograph about the life and death of her dear friend Cookie Mueller: “I used to think I couldn’t lose anyone if I photographed them enough. In fact it shows me how much I’ve lost.” This cruel fact is not lost on Goldin.

The Ballad was a book I returned to again and again. Fascinated by the shifting relationships between Goldin, her subjects and her camera – the ambivalence, trust, oblivion, poignancy, ecstasy, despair and sadness, love and lust.

Since then I have seen Goldin present her images at a variety of events at the Photographers’ Gallery and the ICA and again been deeply impressed by her unflinchingly honest, brave and beautiful work and how it has evolved as she has: from her drag days in Boston, to Lower East Side party oblivion, from empty bedrooms to her more recent poetic, abstract landscapes and film installations.

Her groundbreaking and brilliant work has been influential. And while various photographers, particularly those working in fashion, have appropriated elements of her style none rival the genius of her uncompromising vision.

As I mentioned above, I conducted the interview for the brilliantly innovative Pure – such a fantastic place to work where I met the most brilliant and talented people, it was like going to Warhol’s Factory everyday – which closed and so wasn’t able to publish the following interview.

Seeing as this piece was for a fashion magazine, that industry is discussed at some length by Goldin in this piece. But I think her observations are worth considering and it’s (to me, at least) interesting to hear her talk around topics other than her early life and career as she established herself, which are frequently revisited in interviews with her.

At the time of this interview, which took place in London in January 2002, her exhibition, The Devil’s Playground was showing at the Whitechapel Gallery.

Coincidentally, Goldin has a show in London at the recently opened gallery Sprovieri of recent work, including grids of images featuring new and old work and a slideshow of her pictures of children. I could write a lot more about Goldin and how much her work means to me, but I’ll stop now. Here’s the interview:

CS:Is film still the number one thing in your life?

NG:My number one thing is still to go to a movie. They seem surprised by how long I take to install here because I can spend a week installing a show. There are 350 pictures in this show. Not all are new. Two thirds are from 1999 onwards. I’ve got really prolific since I moved to Paris where I am living permanently, for the rest of my life, until I find another idea.

I have really close women friends here: Valerie, Raymonde, not Joana so much, Maria Schneider, who was always a real heroine of mine who and has now become a close friend. I have very healthy strong relationships with women. I didn’t have so many in New York. My life there was almost entirely about gay men for 30 years.

CS:So that’s the reason you’re in Paris?

NG:That’s a big reason.

CS:Do you find it more sympathetic? Do you find Europe more politically sympathetic?

NG:No place could be less sympathetic to my politics than America. My work is received more intelligently in Europe. I had my first museum showing of my slide show in Rotterdam, in 1983. I love Rotterdam. I love harbour cities in general. I like it much better than Amsterdam which is too much like a postcard. It’s too cute for me.

Rotterdam is more real, it’s got a stomach. In ’83 I started travelling round Europe with my slide show. It wasn’t until I moved to Europe and got accepted in a big way in Berlin in the ’90s that I got acceptance by the big art world in New York. I didn’t really get to be known, or in the market, til ’93 in New York.

CS:Is acceptance important to you?

NG:Yes it was. Now what I like is that other artists know my work and are interested in me or want to collaborate. I’m very flattered when people I respect like my work. It’s like a dream of a little kid when somebody I idolised likes my work.

CS:Like who?

NG:Maria (Schneider). I don’t think of her like that anymore, because I worshipped her when I was young. Like Kiarostami; Jan Fabre the theatre director and visual artist; the Dardenne brothers, Jean Pierre Dardenne and his brother Luc Dardenne, Wong Kar-wai.

Like Yves St Laurent, I don’t know if he likes my work but Pierre Bergé does. Stella McCartney is a big fan. I feel like a little girl sometimes because I don’t hang out with celebrities. I have never got into that. I never courted that but it’s nice when it’s people you respect and they respect your work. It’s thrilling.

CS: In a recent interview with the Observer, you said you were ambivalent about the fashion world and cosmetic industry.

NG: One of my assistants, a British man, says I should find a platform for it. Meanwhile I wear make-up.

CS: It’s a dual edge thing.

NG: I have no ambivalence about myself wearing make-up or designer clothes but I have an enormous ambivalence about what the fashion world has done to women.

CS: Do you know the writer Jean Rhys?

NG: Yes, I read everything by her.

CS: Do you remember the quote from her (I think from Quartet) “the desire to be loved and to be beautiful is the true curse of Eve”.

NG: Ha! It’s not true for me, my life is more important. At this point in my life I’m alone. I don’t think about it a lot. I’ve been alone for about eight years and it doesn’t bother me.

Yes, I need to be fed but the need to be loved by friends has been as important to me than any lover I’ve had all my life. This is part of the reasons that my lovers don’t stay because they are jealous of how much I care about my friends.

CS: Haven’t you recently shot for Vogue?

NG: I shot for French and British Vogue. The British Vogue one featured clothes by Chloe and was shot at Highgate and the John Soane Museum. It came out much better in my opinion. I only did one day and was working with my own make-up and hair people and a model who I’ve known for years.

I like Stella (McCartney) a lot – she’s a very open and warm person. I don’t particularly want to know about her background. We started talking last night about how we should tell each other about our family histories but we haven’t got there yet. Each time I spend with her, I like her better. So I was excited to be asked by her.

I had bought some Chloe clothes in Italy. I was interested and curious about her. I know somewhat about Kate (Moss who featured in the Vogue spread). I always thought that Kate’s look had come from my old friend Siobhan Liddell and some of her friends because they dressed like that about ten years ago.

Unconsciously, and right after that, that whole look sort of came out. It looked exactly like Siobhan and Siobhan actually is – or was – as thin (I think she still is). She has that kind of baby face, a very young face. So I was interested in working with Kate.

At the same time as the UK Vogue one, I did a shoot that took about 40 days of friends and people I admired in Paris, for French Vogue. It included Joana (eight or ten pages) and Valerie. This is how I met Maria Schneider in June and which began our friendship.

I also met Dominique Sanda, who I always worshipped. I also photographed Maggie Cheung – but these didn’t develop into a friendship either – and Maria de Medeiros a Portuguese actress and her daughter.

She played Anais Nin in Henry and June. And Amanda Ooms who lives in London, and who I’ve known since ’89 and my friend Joey from New York who is a gorgeous transsexual.

The shot was about jewellery but that was sort of secondary. It was more like portraits. Joey is almost completely naked and they are taken in hotel rooms or old 18th century hotel rooms that I love.

The pictures were beautiful but the layout and colour-printing weren’t so beautiful. I love lots of the pictures but somehow there was something flat and dead about the way they were printed. But there was a really interesting letter published in the magazine the following month from a woman reader saying it was so nice to see real human beings.

One of the fashion things I ever did was for Helmut Lang for Visionaire magazine and I used people from all genders. People from the age of 18 – like James King – to people like my friend Sharon who’s about 50 or older. People of all different shapes and literally all different genders and my boyfriend at the time and his daughter who was 11. If I were to do fashion that’s what I would want to do?

CS: Does it feel different when you shoot fashion?

NG: Well, that day it didn’t (for Helmut Lang). It was really fun. For Paris Vogue, it was setting up the shooting, setting up the clothes – there was so much involved in the set-up that it literally ended up being 40 days – or it felt like that. The letter was very gratifying. This woman acknowledged it was the first time she had seen in a fashion magazine real people of different shapes and ages.

If I do continue to do fashion, I would want to radicalise it, refuting the whole idea that there is only one way to look; that women have to be so skinny to look good; that they have to be 12 years old and wearing clothes that only women in their 30s and 40s can afford. Plastic surgery is distressingly popular and I feel that the fashion industry has killed tens of thousands of women over the years from anorexia.

I used to live with Teri Toye in the ’80s – a really gorgeous transsexual. She won Girl of the Year in 1986 (I think) as a Chanel model and she introduced this whole way of slinky, slow-motion modelling. It was amazing that the girl of the year was actually born male.

It’s so rare to see a woman’s sexuality, real female sexuality, either in the shows or in the clothes. And in Paris now, when I walk into stores and the shopgirls literally say to me every time, “We don’t have anything in your size”.

The only time this happened to me before was in Jil Sander in Berlin where they said, “We have nothing that will fit you.” I said, “Yes, you do.” And I found something great. This happens to me in Paris again and again and again. They don’t carry anything over size 40 which is nothing, because I wear a size 42 or 44 but that’s hard to find in Paris among the designer clothes. All stores are like that. And I say, “Aren’t you ashamed of yourself?” And they say, “not at all”. But I say, “Not in the rest of the world.”

It’s a hideous feeling to go round shopping and even feel like you are a freak. In America, more than half the population are overweight. It’s not healthy and I’m not proud of that but I don’t hate having a woman’s body. I’m not ashamed of my body and you know everything in the fashion world, if I was vulnerable to it, could drive me crazy. I think it produces so much self-hatred.

I remember so many girls when I was growing up who hated the way they looked. My work shows the beauty in so many different kinds of people because I never photograph anyone who I don’t think is beautiful.

I never take an intentionally mean picture. I won’t show a picture where a person doesn’t look beautiful. There are days when everyone in the world looks like a Diane Arbus to me.

She’s a genius but her work is completely different to mine. But on those days I don’t use my camera. I feel like if I started to use it that way, it would be like a sin almost. I never show people ugly pictures I take of them. I usually destroy them. So even if I like it, and they don’t, it doesn’t get shown.

The main thing that I want to say in this magazine is that I don’t think women are at their most beautiful in their adolescence or in their early 20s. You know it’s said that you make your own face. So you don’t really have a face until you are 30 or your mid-20s. When you are starting to grow up and show your character in your face. I think it’s obscene that many people are starving to death from anorexia.

It’s been said many times, it’s trite. But when so much evil is going on against, for example the Afghani people, where women are being so oppressed that a woman’s body is a battlefield.

One of the things I love so much about Valerie is that she inhabits her body so completely. She has no self-consciousness about having stretch marks or having given birth. It’s just so amazing that she has nothing to hide. Whereas all these other women see every little – supposed – imperfection – anything irregular is seen as an imperfection.

Actually, I think what is being shown as beauty in fashion magazines right now has become particularly ugly. This kind of straight, blonde very conservative.

American magazines are becoming very patriotic beyond belief to the point that I can’t live there any more. I had said that when the first Bush got elected that I would leave the country. And when the second Bush wasn’t even elected properly.

I wasn’t there when the city was bombed but it seems to have changed my friends. Some people have become a lot more conservative but I can’t really speak about that because I wasn’t there. I feel compassion for their pain but it distresses me to see them all become more patriotic.

CS: How do you feel about appropriation of element of your style in fashion photography?

NG: In a way, it’s an homage. But I didn’t really know about it at first. But then when I started living in Berlin in the early ’90s, I started getting ID and Dazed and Confused. I was shocked how close things were to my work.

CS: Nothing in those pictures has the power to move you though.

NG: Well, it’s all set up. I never, never photograph someone getting high to sell clothes. I was called, at some point, the person responsible for “heroin chic”.

I didn’t have anything to do with “heroin chic”. I never thought heroin was very chic. I did maybe when I was 18 but I got over that pretty quickly. The idea that a fashion photograph could make you cry doesn’t happen. And I’m proud to say that my slideshows can make people cry.

CS: I love the narrative quality of your images. There is a short story in each one.

NG: I don’t think I am going to do pictures which are anything like Renaissance art. I’m very influenced by a lot of things, but my chief influence is my friends and what I see and what I feel and my own experiences and memory. And the things that I look at include Renaissance art. I’m obsessed with churches and paintings of saints.

CS: You’re not Catholic, of course.

NG: I have the freedom of seeing it with a non-Catholic eye without the guilt. No Jews have our own guilt, that’s why we have psychiatrists – the Jewish version of a priest. As a non-Catholic, and since I was a child, I have been obsessed with the ritual and the beauty of Catholic art. I look at Renaissance art all the time. That’s where I got the idea to paint the walls of the gallery with varied colours (at the Whitechapel show). I tried to figure out how all these Renaissance paintings manage to work together.

And after that, I start to paint my walls. And I’m heavily influenced by films.

CS: Who has influenced you recently?

NG: Cassavetes, Killing Of A Chinese Booker, Opening Night are my favourites. Gena Rowlands is fabulous. The work of early Antonioni, Orson Welles and Pasolini, I love Roeg’s film Performance. I saw Darling the other night, which was amazing. I love all the Hollywood women. I saw all the films when I was a teenager. Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures.

The film maker Vivienne Dick had a big influence on me. I found her eye was very close to mine. I think we see things very clearly.

CS: Are you still taking self-portraits?

NG: No, not recently.

CS: I have always wondered how you managed to never show your camera when you were shooting yourself.

NG: There are ways of angling the camera. I don’t just use a tripod. The only time I did that was in ’88 when I first came out of detox, I spent every day doing self-portraits to fit back into my own skin. I didn’t know what the world looked like – what I looked like – so in order to fit back into myself, I took self-portraits everyday to give myself courage and to fit the pieces back together. I used a tripod then.

I was recently interviewed for radio in relation to the Thanksgiving show (2001) at the Saatchi gallery that I was part of. The interviewer said that people in London were very disturbed that I showed a picture of myself battered (Nan One Month after Being Battered, 1984) and they thought that I set it up.

I was accused of deliberately putting on a wig for that particular picture. And also because I have some make up on they think I must have set it up. Of course I was wearing make-up, I never went anywhere without red lipstick for 25 years! It was a form of self-preservation for me to continue to wear lipstick even though my face was broken.

When I started photographing my boyfriend of years ago, Brian, I realised I had no right to photograph other people having sex if I wasn’t prepared to take them of myself too.

The thing that drives me most crazy in the world is not to be believed. If I say something honestly, generally, I am being completely honest and don’t tell me I am lying. It drives me crazy to be told I set up my pictures. How does it benefit me to lie? I guess they are afraid to believe it and are afraid to look at it.

CS: I think you look different in every picture of yourself.

NG: I think that’s even more apparent in the portraits of Valerie. I took 15 pictures of her and you see so many different sides of her. Like the pictures I used to take of Siobhan.

CS: In this culture women aren’t allowed to display all their sides, for instance to show their anger, sadness, pain.

NG: One of the major things I really want to work on now is female rage because that’s not dealt with at all – and I have a lot of it. A lot of women I respect have it too, you know. I think it killed my sister as the times she was living in were so conformist. This is a subject I really want to deal with. I want to start making films about female rage.

CS: Is this going to be a documentary?

NG: I don’t know. I am going to collaborate with Valerie who is my closest friend on one about my sister for a big show in a mental hospital (Sisters, Saints and Sibyls at La Chapelle de la Salpêtrière ) next September in Paris where they invite an artist to show. This year it was Jenny Holzer. Usually people just do their own work.

But I want to deal with the place and what it means to show in a mental hospital. This is what I am working on at the moment. I like using different mediums – not just photography and slide shows, but also film. There was a saint named Barbara and the story has some components which relate to my sister’s story, who was also called Barbara. There will be big cibachromes of empty spaces and still lives and a kind of emptiness.

I’ve become really interested in the landscape but not as landscape but more as it relates to mood and how we live and how the outside impacts on the inside. I didn’t really look at the outside world during the years I was photographing the Ballad as I was locked inside my house and I lived totally inside. The only time I went out was to go to bars at night and all the pictures were taken with a flash because there was no light at all. However now I’m very interested in light. It’s the first time that my work has become at all metaphorical – or allegorical.

CS: Do you feel the allegory when you are shooting the pictures or is it in the viewing?

NG: More in the viewing. But I’m very much interested in water and women in water. I’ve been photographing that for years although I didn’t really know it at the time.

I usually work really instinctively and it’s afterwards that I think about what it means. I don’t know consciously that I have these themes that run through my work. This show (“Sisters, Saints and Sibyls”) I’m talking about is the first time I’m working on ideas really. When I put my big retrospective together in ’96 (for the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York), I saw that there were all these pictures of people inside looking out. All these pictures of women in water and mirrors. I don’t know what it means.